Archaeomythology term paper,

New College of California, San Francisco

Spring 2006

The Pomo people are the descendants of ancient tribes living in the north-central part of California, for the last several thousand years. Their territories extended throughout the areas known today as Sonoma, Mendocino, and Lake Counties.

The Pomo originally spoke seven distinct languages (answers.com), with only 3 surviving. They “were originally linked by location, language, and other elements of culture. They were not socially or politically linked as a large unified "tribe;" Instead, they lived in small groups ("bands"), linked by geography, lineage and marriage” (answers.com). More than 70 different tribes existed within what is known as Pomo country (Cloverdale Historical Society).

“In certain parts of the California countryside there are large, sometimes peculiarly shaped boulders, shrines that are said to contain within them the power to grant fecundity to women who follow the appropriate procedures at the site. Such shrines often represented mythic figures, commemorating events of the distant past. In this light birth moves from being a purely natural biological event to a phenomena inspired purely, at least in part, by supernatural means” (Precious Cargo).

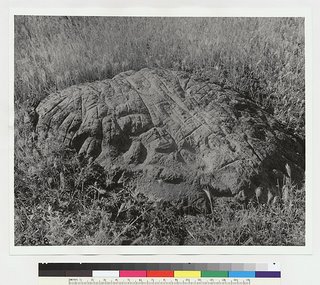

“A Pomo ritual which may have included movement through rock involved the ethnographically-documented petroglyph boulders known as "baby rocks." The spirits of future children dwelled in these rocks, and were born to parents who followed the proper ritual. The wilderness was full of power capable of affecting human fertility, and certain springs, trees, gopher mounds, rocks, mud, and snakes could cause pregnancy. In addition, a female effigy made of clay, and called "Earth Woman," was given to sterile women to insure conception. Apparently, the powers affecting fertility resided beneath the surface of Mother Earth” (Parkman).

An Eastern Pomo woman has been fasting for the last four days, other than a small amount of water, or maybe “a little mush after dark.” (Childbirth Traditions 12, Loeb 247). On the fifth day of her fast she began a solitary journey (CT 12) at daybreak to one of the Gawik Xabe (child rocks) located throughout Pomo country.

An Eastern Pomo woman has been fasting for the last four days, other than a small amount of water, or maybe “a little mush after dark.” (Childbirth Traditions 12, Loeb 247). On the fifth day of her fast she began a solitary journey (CT 12) at daybreak to one of the Gawik Xabe (child rocks) located throughout Pomo country.She has brought with her a small flint knife (Loeb 247, CT 12). Counterclockwise, she walks around the rock four times and then reverses in a clockwise direction four times (Loeb 247). She then performs several ritual movements in precise order (CT 12). She faces the carved surface of the rock, raises both hands, then stretches them out before her, her fingertips in line with her eyes. She “then draws them in, fingertips on her breast, fingertips meeting.” Four times this is performed. She bends on her knees four times, and finally sits back on her heels (Loeb 247).

The woman removes the flint knife and pretends to cut the rock four times. Four more times she actually carves the rock creating a pile of rock dust (CT 12, Loeb 247).

If she lived on the central coast she would carve a straight line if she desired a boy and a curvy line if she wanted a girl.

“Taking the dust she has ground from the cutting, “she decorated her body with two lines from her lower lip to her naval, a horizontal line across her chest, from armpit to armpit, and a circle where the horizontal and vertical lines intersected. A dab where the [art of her hair began on her forehead completed the ritual markings” (CT 12).

Without any set prayers to guide her, the woman asks the rock for a child.

“She rises and beginning again with the lifting of hands, goes through her ritual four times. Then four times she walks about the rock counterclockwise, then clockwise four times. She stops where she has been crouching, turns her head to the left four times and then goes home. Four times on the way she stops and turns her head to the left, but on no account must she look back. All this must be kept secret from everyone” (Loeb 247).

In the Northern Pomo version of the ceremony the woman might climb on the rock as if it were a man. She stayed on the rock maybe an hour, praying to kudi homTo kawi (good bring me child) (Loeb 248).

In another variation Jeanine Davis-Kimball described the Pomo who called their rocks ku’ kabe. A couple would go to the rock together, pray, make an impression on the rock, and then have intercourse, although it wasn’t stated where (Mahaffey).

The designs carved onto the stone often took the form of depressions, grooves and cupules, suggestive of the reproductive organs (Sacred Sonoma). According to archaeologist David S. Whitley, the woman was performing “a symbolic act of ritual intercourse with the rock” (Whitley book, 98).

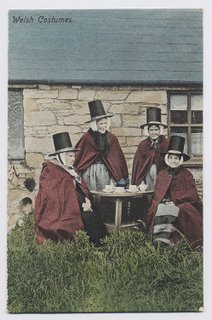

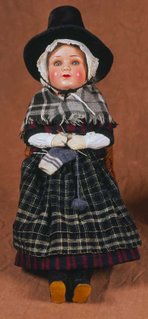

The Eastern Pomo called conceiving children through magical means "kus doolki." One method used by the Eastern and Northern Pomo were dolls (the Coast Central people had never heard of using dolls - Loeb, 247). The color red sometimes appears metaformically in these rituals. Unlike the Eastern dolls which were usually white clay and wood, the Northern dolls were called po kabe gawi.

Edwin M. Loeb’s (the famous ethnographer of the early twentieth century) “Northern informant said that this method of getting children was not a certain one, as it was just asking, i.e., prayer. However, “going to the child rock was a certain method, i.e., magic” (Loeb 247). (Aginsky double-checked Loeb's ethnographies in the field and found his information to be accurate).

Prayer always seemed to be the first choice and was described by informants as the most direct way to go (check reference).

In addition to baby rocks (the most common method) and red rock dolls, the Northern Pomo also had a tree that they would go to, but the baby rocks were considered more desirable because the trees were thought to “give children with small eyes” (Loeb 248).

Bowen, a North Pomo informant said, “A woman can’t get children simply by having sexual intercourse. She must do something else besides. She has to make use of a certain tree or rock, or the sacred dolls or bull snake. She must also pray.”

Austin Creek Basin, Sonoma County

Austin Creek Basin, Sonoma CountyLike most indigenous Californians Pomo cosmology consisted of three worlds: the upper world, lower world, and middle world. People lived in the middle world, while supernatural power dwelt in the upper and lower ones. The middle world where humans lived was further divided into ‘civilized’ community and villages, organized by culture, contrasted by the wilderness, not under direct Pomo control, and permeated with spiritual energy. Senior state archaeologist, E. Breck Parkman, has examined the “supernatural frontier” of Pomo cosmology:

“Within Pomoan cosmology, there existed, a dualism, which contrasted the concepts of culture and nature, domestic and wild, and community and wilderness” (Parkman).

Extending from the wilderness, into ones community, “the supernatural realm interfaced with the community in two main areas: menstruation and death.” Parkman continues, “Through their ability to give birth, women were in constant contact with the supernatural realm.”

“Once Outside,” the village (known as Inside, as in inside a house) and into the wilderness the boundaries of this frontier, “manifested itself cognitively in a number of areas, including rock, water, elevation, menstruation, and death” (Parkman).

Cultural theorist Judy Grahn describes these sacred landscapes as metaformic. Grahn describes a metaform as, “an act or form of instruction that makes a connection between menstruation and a mental principle,” (Grahn 20) “a physical embodiment of metaphor in which menstruation is one part of the equation.” She says the human mind uses metaphoric imagry,” or “external measurement” (Grahn 19). “Our ancestresses taught via menstrual instruction,” she says, “through rituals that embodied ideas based on menstrual information.”

“The ancestral sisters stepped out of the dense animal matrix of primate consciousness on a bridge of creature metaforms – living beings that embodied ideas developed through seclusion rites. The menstruants inner connection to lunar cycles pulled her mind outside itself, and she cast it onto other natural beings, entraining her blood imagery with their shapes and habits. Metaform, the middle form between menstruation and an idea, was applied to the wilderness, with certain plants, animals, and other creatures singled out to embody instructive and connective principles. Based in physical life, in earthly experience and observation, the metaforms between creatures and landscape became an external expression of thought, allowing us to externally communicate ideas of measurement, origination, and deity” (Grahn 51). Grahn notes that,“Coyote created menstruation and death for the Miwok people of California” (Grahn 125). According to Judy Grahn’s Metaformic Theory, birth and death were seen as aspects of menstruation, “parallel menstruations” (Grahn 123).

Parkman points out that, “water was another aspect of the supernatural frontier. Most Pomo rock art sites occur adjacent to or near water sources.” Grahn adds that from an indigenous perspective women’s “blood was analogous…to water" and that “all water was comprehended in terms of menstrual flow” (Grahn 24)

Known or suspected fertility rocks within Pomo country that were surveyed for this report, including the State of California and/or the University of California ID # (if known):

Austin Creek Basin, Sonoma County

CA-MEN-1912, Spyrock Rd., Mendocino County

MEN-875 - Knight's Valley, near the base of Mt. St. Helena, somewhere in East Sonoma (or Mendocino?) counties. One of only two of the seven ethnographically documented baby rocks positively I.D.’d through ethnography and located and recorded as archaeological sites (Hedges). BELOW:

Cloverdale, just north of town on the Russian River, “a soft bluish-gray, metamorphic stone, probably chlorite schist (Hedges). On the eastern side of the rock are cupules, horizontal incised lines and “incised notches on raw edges and natural raised surfaces.” Some of the glyphs are now covered with a,“golden-brown lichen.” (Hedges) BELOW:

LAK-34, Bachelor Valley, Lake County, one of two sites studied by Henry Mauldin.

Red Rock Island, Clear Lake, studied by Henry Mauldin. Very metaformic and very reminiscent of Rigoglioso’s observations of Persephone’s Sacred Lake, Sicily’s Lake Pergusa.

Clear Lake (is probably the oldest lake in North America):

“Red Rock Island is named for its red volcanic formation. It was once the site of a large and well-used fishing village on its eastern slope. On the boulders of this island are many pits made by the natives. Most are small with a few large ones. It is generally accepted that they were dug either to produce rain or to stop it. Some anthropologists hold that the squaws made these holes in an appeal to the gods to grant them fertility” (Mauldin 30-31).

Parkman’s description

“LAK-30 is located on Slater Island at the southeastern corner of Clear Lake, in Anderson Marsh State Historic Park. The approximately 30-acre island represents one of several loci of the ethnographic village of Koi. When viewed from the south, Slater Island looks like a lush green mound rising from the marsh. A dark ridge of rock cuts across the island, rising to a height of about 7 meters. Near the center of the ridge is an area appearing red from a distance. The color is derived from lichen growing on the rocks. A dark area immediately below the red is the entrance into a deep crevice. A closer inspection of this location reveals several pitted boulders adjacent to the crevice, and thirteen parallel red lines painted on an exposed vertical face above and slightly to one side of the crevice” (Parkman).

Dry Creek Valley, Sonoma County, 31 cupules, now underwater of the dammed Lake Sonoma.

Several baby rocks in the Dry Creek Valley were inundated by the waters of Lake Sonoma in 1984 following the construction of Warm Springs Dam. Others were relocated by the Army Core of Engineers. Many Pomo people feel that removing these rocks to other locations rendered them useless, as their original locations were the key to their power. (Childbirth Traditions 13).

Child rocks are usually associated with the Pomo in North-central California, but known or suspected child rocks have also been found, “as far north as Port Ford, Oregon and to the southern end of [California’s] Central Valley,” (Express) including:

Suspected stones in Contra Costa and Alameda counties, and the greater Bay Area

CA-CCO-125, Alvarado Park, Richmond. BELOW:

U.C. Berkeley, Native American site #152, aka CA-CCO-152, Baxter Creek, Canyon Trail Park, El Cerrito, schist. Wound up as part of a childrens play park, currently being reconstructed as a Native American interpretive park (O’Brien).

“It's located in a park, near a stream. It's about eight feet long and four feet high and is soft in some places, hard in others, and pockmarked with cupules that give it the look of a giant sponge. Some of the cupules are as small as depressed thumb prints, and others as large as soup ladles. From just the right angles, and in just the right light, the rock slopes down the middle and converges in a feminine manner, as if Georgia O'Keeffe herself had shaped it” (Express).

Mira Vista Park, Richmond, Contra Costa County, East SF Bay Area

a suspected one in Kensington (between Berkeley and Albany) (Express)

Ring Mountain, above Tiburon in Marin County (Express). BELOW:

Santa Clara County, Almaden Valley. Contains “a preponderance of female symbolism” (Archeo-tec) BELOW:

The famous archaeologist, Robert Heizer said, “this type of petroglyph occurs sparingly in California but is found in all rock art regions. Identical rocks are found in many parts of the world and the style may well be the oldest in California.” David Whitley agrees, “The Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition” is “the one pan-California rock art tradition.”

Ethnographic data associates most Pit and Groove tradition in California with female fertility (Whitley book, 98). The greatest amount of ethnographic information available on the subject is for the region just North of the San Francisco Bay although, “there is also evidence supporting a connection between female fertility ad conception and the Pit and Groove Tradition, generally in the remainder of California” (Whitley book, 98). For instance, “Young Yokuts girls,”on the border of the San Joaquin valley and the Sierra foothills, “would create cupules during puberty ceremonies sometimes painting them with red pigment” (Whitley book, 100). (Metaformically the paint was the menstruation of the earth (Grahn 76)). Ethnographic data also revealed that “in the region of the southern cupule variant,” in the Tehachapi area, “the Sierra Kawaiisu women desiring conception would grind and then swallow a small amount of rock dust from cupule sites” (Whitley book, 100).

Whitley and Heizer noted that the only exception to this pan-Californian tradition was in Northwestern California, among the Hupa, Karok, Tolowa, and Shasta Indians (Heizer sourcebook), as “Northwestern California was different culturally from the rest of the state” (Whitley book, 98). Actually they carved cupules into rocks like the rest of California but for a different purpose: weather magic.

However, the last female shaman, in (Northwestern) California (Tela Star Hawk Lake) is of, "Yurok-Karuk-Hupa...Chilula and...a small part...Irish," she says, "In our traditional belief motherhood and childbirth are considered a sacred obligation and a natural part of a woman's cycle and role in life. Pregnancy was approached with respect and the young women were taught to look forward to childbirth as a spiritual experience, not to fear and dread it. There were even special forms of assistance that could be provided to women who had difficulty becoming pregnant, or for those who were considered barren. For example, according to myth and legend there is a sacred rock known as the Creator's Basket Rock that a woman could make a pilgrimage to, and where she could offer prayers, cry out to the Great Creator, and ask for assistance. The myth that teaches us about this sacred place also instructs the woman on the proper way to prepare for this visit, what to say in terms of a prayer, what to offer in exchange for assistance, how long to stay at the site, what herbs to use while in prayer and meditation, and what to do afterward. Legend has it that the most sincere attempts were successful, but such places are held in strict secrecy. Unfortunately, some of these places have already been destroyed or desecrated by commercial developers, the timber companies, the U.S. Forest Service, and tourists (Hawk Woman Dancing with the Moon).

Archaeologist Ken Hedges maintains that the rock art of Northern California is more complex than originally believed and that “the Pomo analogy” is best reserved for those instances in which the physical description of the site closely matches that of known baby rocks. Hedges disputes the notion “of a universal pit and groove style which somehow indicates a widespread relationship among cupule sites,” despite his admission that we have so much specific ethnographic information on some of these sites: “the rock carvings of this area [North-central California] exist in one of the few areas of the continent where we have specific ethnographic information on the function of some of the sites,”yet acknowledges that, “the manufacture of cupules per se is one of mankind’s oldest and most widespread artistic activities (Hedges 57).

The fertility rocks that have been discovered in the East Bay, and the greater Bay Area have been a surprise to archaeologists like Dr. Paul Freeman, since the East Bay rocks are usually associated with Hokan-speaking cultures, like the Pomo, but the rocks in the East Bay are in Ohlone territory (Express), and are thought to have been used, “long before the movement of the present day Ohlone (Penutian speaking) peoples into the Bay Area” (Marymor).

AN ANCIENT TRADITION

Researchers dig several feet beneath the surface of a suspected rock, to see, “how far beneath the surface the cupules appeared on the rock. The further the markings went, the greater the rock was revered over time.” On the El Cerrito rock, CA-CCO-152, markings were found more than four and a half feet below the surface. California State Hayward, adjunct professor Roger Kelly says, “the original ground level was a lot lower at this site and the rock was revisited again and again over many generations for perhaps thousands of years” (Express). Archaeologist, Kathy O’Brien said, although its impossible to know for sure, some of the etchings may be 8000 years old (Lopez 2004).

Although it is likely that specific aspects of the symbolism of “Native California rock art did change over time, the widespread unity of the ethnographic pattern speaks of a tradition with considerable time depth. It is unlikely that the great similarities in the production and meaning of rock art from such disparate regions as the Columbia plateau [between the Cascades and the Rockies], the Great Basin, and native California would be so strong if they did not reflect a tradition of great age” (Whitley book, 101).

A Google Image search on “cupules,” “cupmarks,” or “cup and ring,” designs reveals remarkably similar patterns and images, literally all over the world. This Google search led me to discover the Bradshaw Foundation’s sponsoring of the first ever International Cupule Conference in Bolivia, July 2007, because cupules “are one of the most common forms of rock art and have so far received very little attention” (Bradshaw, International Newsletter on Rock Art).

Another page at the Bradshaw foundation states: “Cupules can be found in rock art sites on every continent. They represent some of the earliest and most fundamental art forms, as well being executed today in traditional societies.” To see more photos of cupules on fertility rocks around the world, including Australia, Hawaii, and Scotland, click HERE

The book, Ancient Celtic New Zealand, and it's corresponding websites by Martin Doutré, contain astonishing photographs of similar rocks, which can be viewed HERE and HERE.

In a paper entitled, "The Motif of Birth In Prehistorical Artforms," demonstrates that the earliest rock engravings are connected with the topic of birth.

“In Brittany and Normandy farmer's wives, who lacked an offspring, are to have spread butter or honey in bowl pits, in order to receive a child trough this offering. In Germany the people's faith in the cups was so deeply rooted that even the Christian churches gave it consideration. During the building of the St. Gotthard church in Brandenburg two sandstone blocks were especially added into the portal walls, at which the population could grind out cups and grooves. The rock powder from such bowls was supposed to be a means by which young married couples could make sure of child blessings. The bowl pits of many stone surfaces on Hawaii which are called Piko-holes there, are connected closely with the human birth. In order to express the desire for a long life of the child, parts of the navel cords of new-born children were deposited there as an offering.

The earliest rockcutting that certainly reveal a content of the abstract dots and lines, are supposed to show the female abdomen. These vulva-portraits are surrounded by multiple bowls and occasionally also the mouth of the uterus is symbolised by cups. The Vulva motif is possibly a direct natural representation of objects and in former times possibly already a single cup had this meaning. Both the production of rock powder as well as the abstract representation of a vulva by a cup can have led thereby to the so-called bowl stones, which can be found on all inhabited continents. In Pomerania bowl stones were called "swan stone" or "stork stone", in Switzerland it is told that the small children come from these bowls.”

CLICK - HERE IS AN ILLUSTRATED LIST OF "CUP & RING" "FERTILITY STONES" in Yorkshire, England

The Dobrudden Stone at Baildon Moor, in Yorkshire, England. BELOW:

In her book, The Language of the Goddess, Maria Gimbutas, highlighted two photographs of large stones covered in “cupmarks,” which are sometimes circled by a carved ring border (Gimbutas 61,312). “Predominant features of deliberately modified rocks and human-shaped stones throughout Europe, particularly in the west and north, are small round hollows, the so-called cupmarks. They appear by the hundreds, alone or in association with eyes and snakes. Occasionally in anthropomorphic stone – the Goddess – is solidly covered with them. Not infrequently they are surrounded by single, double, or multiple circles…A cupmark is a miniature well… In prehistory and in folk memories, well and cupmark were symbolically interchangeable” (Gimbutas 61).

Gimbutas noted a similar usage for the stones and their cupules:

“In Niederbronn, Alsace, where in Celtic times Diana was worshipped as the Goddess of sacred wells, to this day women carry water from the mineral spring to nearby mountains. There they pour it over stones with circular depressions to ensure pregnancy” (Gimbutas 110).

Archaeologist, Jeannine Davis-Kimball describes a stone sculpture in Northern Ireland that was in the form of a female (including “an inverted V,” representing a vulva) with a “rectangular depression at the top,” filled with rainwater. Kimball’s friend said, “This is still used as a fertility font by the local women who want to get pregnant and can’t.” Kimball’s friend accidentally touched the water and later found out that she had become pregnant right after this took place (Kimball 204).

These rocks in Borama, Somaliland, Africa are said to be able to give barren women babies, if they sit on them. BELOW:

In addition to small, stone sculptures carved by the Yarmukians (the stone age culture of Israel/Palestine and the Levant) in the shape of females, with exaggerated hips, plump faces and holding their breasts; River pebbles have been excavated, “which are carved with faces and female sexual organs, the verdict is likewise that they are symbolic of some fertility cult. Because literal sources did not exist in these Prehistoric times it is hard to shed light on the meaning of these figurines and carved pebbles - the Bible or any Near Eastern text were produced long after the Yarmukians were replaced with other cultures” (Schaalje). BELOW:

The use of stones (often in conjunction with water) for the lack of fertility, or for childbirth, breastfeeding, or even birth control (see Aginsky and Loeb) appears to have been common around the world. This excerpt (sans footnotes) from Gary Varner’s book, Menhirs, Dolmen and Circles of Stone: The Folklore and Magic of Sacred Stones, lists numerous examples:

“In Burgos, Spain a fountain dedicated to Saint Casilda was reported to have the powers to make a woman fertile. If a stone was thrown into the waters a baby boy was assured and girls were ensured if tiles were tossed into the fountain. In Armenia it was believed that sterile women would frequent the stone passes in Varanta. Legends say that “if she is to have a child the stone enlarges and lets her pass but the opposite happens if she is not to have a baby.” (9)

Near the Yorkshire village of Ratho, seven miles from Edinburgh, the Witch’s Stone, a large sloping boulder (now destroyed) with ancient cut marks was used by women who slid down the stone in the belief that the stone would assist them in conceiving. A similar stone used in the same way is located in Kings Park, Edinburgh. The stones were highly polished by the many women who slid down them over the years.

A fertility amulet, also known as a pregnancy stone, was in use in Italy and recorded by Walton McDaniel in 1948 in the Journal of the History of Medicine:

The amulet, “in the shape of a womb…a limonitic concretion or brown hematite, which, on being shaken, produces a sound…the prospective mother wears it nine months, fastened to the right arm, but then, at the arrival of the first pains of partition, she transfers it to the right thigh. Women hire the use of these stones from a midwife, if they do not possess one of their own as a family heirloom. Although these amuletic objects might seem to be somewhat pagan, grateful mothers do not hesitate to deposit them as tokens of success, as ex-votos in a Christian Church.” (10)

Difficult childbirth was avoided by wearing, or keeping close, stones the color of the sea, such as beryl. Stones with holes in them were especially prized and if hung over a woman in labor the birth would be much easier as it was viewed as a protection against evil. In ancient Roman times it was believed that a stone used to kill a powerful animal (or a strong man) also had the power to make childbirth easier. The stone was thrown over the house where the woman lay in labor. (11)

For those worried about the inability to conceive, it was thought collecting stones from the property of couples with many children could reverse the condition. This belief was still present in 1950’s Arkansas. (12) In ancient Egypt it was a practice to make scratch marks on stones in the belief that by doing so pregnancy would be induced. (13)

In Greece and Scotland women desiring children would wade into the sea and then pass through large water worn holes in nearby rocks. Passing through stones is commonly seen throughout the world’s folk medicine traditions. It is a passing through dimensions in an attempt to “pass on” or transfer illnesses and to obtain power and health. Small stones found with naturally occurring holes in them have been especially prized for their magickal properties and they are believed to be linked directly to the Goddess. In North Carolina holed-stones worn by pregnant women eased childbirth and in Northumberland during the early 20th century holy, or holed stones were placed around a horses neck to protect it from disease.

One of the most famous holed-stone is that of Men-an-Tol, near the healing well of St. Madron’s in Cornwall, England. At least through the 18th century, and most probably well beyond that time, persons with back and limb pains would crawl through the hole in search of a cure. Children with rickets were also passed through the stone. For pains the individual must pass through the hole either three or nine time, against the sun, or widdershins. Children with rickets could only be cured if they passed through to an adult of the opposite sex.

Other important holed-stones are the Tolvan Stone, also in Cornwall. At the Tolvan Stone children were passed through the hole nine time, back and forth through the stone. To ensure that a cure was obtained it was necessary for the child to pass through on the ninth pass on the side where a grassy mound was located. The last part of the ritual was to lay the child to sleep on the mound with a sixpence under his or her head.

Rock crystal was a tool used by the Apache Indians to prevent pregnancy. According to early ethnologist Morris Opler, “rock crystal is used as a medicine when a woman does not want a child. The rock is ground up fine, and some of the powder is put in a drink. There are prayers and a ceremony connected with this, but I do not know them.” (14)

New mothers who had difficulty breastfeeding frequented certain holy stones in Armenia. According to Lalayan the women would be taken to these stones, which were naturally shaped like breasts, drink the water that dripped from the stone and wash their own breasts with the water. Afterwards they would pray and light candles in front of the stones. (15)”

In The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth, Monica Sjoo and Barbara Mor point out that:

Ancient people knew that a child is not only the product of human sex; children are also the offspring of the earth spirit joined with the astrological influences existing at its conception and birth. Earth was considered to be the home of children before they were born. In Africa and Australia, for example, souls waiting to be born were believed to live under the earth or in rocks. Unborn children lived in fountains, springs, lakes, and streams, or in trees, bushes, and flowers, waiting to be born as human beings through the joined energies of the earth and moon. Festivals dedicated to the Goddess were the favorite times to conceive children. The moon's monthly waxing was beneficial to an infants growth, and there were baptism rites where the baby was exposed to the moon, sun, and earth, incorporating the newborn within this celestial sphere, or "family." In this way, both Bantu Africans and Native Americans linked the social, biological, and spiritual worlds (Great Cosmic Mother, 152).

WATER

Gary Varner says that the links between standing stones and sacred waters have an ancient and “intricately woven,” relationship. “Stones, in themselves steeped in myth and hidden meaning, are inextricably linked to sacred water.”

"Sacred stones in association with specific holy wells are also common. One such well-stone combination is found at Whitstone, England. Whitstone is a name derived from a white rock located on the south side of the nearby Whitstone church. R.A. Courtney, a noted pre-World War I antiquarian, wrote “the Church is dedicated to St. Nicholas, and in the churchyard is a well commonly known as St. Anne’s well. It is said to never have been known to fail; and it would show that the Church is but the successor of the sacred white stone; the water from the well being used for baptisms. It may be remarked that the saint of the Church is a male, the well a female; and, if my theory is correct, the stone represented the lingam, the well the yoni.” (25) Another megalith with a long history of connected ritual is the dolmen called La Pierre à Berthe located in a field next to the village cemetery of Pontchâteau in Brittany. According to Aubrey Burl, it was believed that the dolmen would cure gout if one approached it on one’s knees. “Up to the 19th century," wrote Burl, “pilgrims would go from the fountain by the church to make their devotions at the stone.” (26) The fountain, or well, connection to the standing stone had an important part in the perceived cure received at the dolmen. Unfortunately, the dolmen was blown up in 1850 by a treasure seeker.

As the Hupa Indians of Northern California ritually washed certain standing stones called “story people” to change the weather (27), so too did the fishermen on the Isle of Skye. W. Winwood Reade, in his classic The Veil of Isis, or Mysteries of the Druids, wrote “in a little island near Skye is a chapel dedicated to St. Columbus; on an altar is a round blue stone which is always moist. Fishermen, detained by contrary winds, bathe this stone in water, expecting thereby to obtain favorable winds; it is likewise applied to the sides of people troubled by stitches, and it is held so holy, that decisive oaths are sworn upon it.” (28)”

“The stone is also anciently associated with sacred wells and this account may be one of the truly surviving Pagan practices recorded in Ireland in the 19th century.

"Rain rocks" were utilized by shamans as tools to control rain and weather. Rain rocks in Northern California were inscribed with meandering lines, grooves, pits and representations of bear claws and paw prints. The Shasta Indians in the Klamath River area carved long parallel grooves on rain rocks to make snow fall, and cupolas to produce rain. To stop rain they covered the rain rock with powdered incense-root. According to rock art researcher Campbell Grant the Hupa Indians of California “had a sacred rain rock called mi. By this rock lived a spirit who could bring frost, prolong the rainy season, or cause drought if he was displeased.” (30) The Hupa would cook food next to the rain rock and provide a feast for the spirit to ensure that the spirit would continue to help them. “If the end of a rainy spell was needed”, continues Grant, “powdered incense-root was sprinkled on the rock.” (31) Rain rocks were fairly universal among early cultures. In Australia’s Northern Territory it was “essential” for certain types of rocks to be scratched to ensure rain. (32) Although rarely found in Southern California, a five foot rain rock marked with hundreds of small, drilled holes was located on the slopes of Palomar Mountain in northern San Diego County. The site was originally a proto-historic Luiseño village called Molpa. (33) Just below the rain rock is a small spring, which was a steady source of water. Because the decoration or alteration of rock material is difficult to date we do not know when the use of “rain rocks” began. We do know that the Tolowa, Karok and Hupa tribes on the North Coast of California used rain rocks predominantly to control the weather at least from 1600 CE and the practice continued into the early 1800’s and may in fact continue today. (34)”

Such sites have usually been considered by shamanistically oriented peoples, as “liminal” space. The Pomo were no different. Merriam-Webster defines liminal as “a sensory threshold.” A liminal space connects two different worlds or dimensions together, such as a boulder residing between land and a creek. A liminal creature such as a water bird might connect sky and water, or sky and earth, or the middle and upper worlds. A snake might connect the middle and lower realms.

A UNIVERSAL TRADITION: WHAT'S THE CONNECTION?

Archaeologist, Whitley, states that in order to understand the symbology and origins of "pit and groove" rock art “requires knowledge of Native California shamanistic symbolism.” Although this art was not made by “shamen” per se. (whitley book, 98).

Pomo women may not have been THE shaman for the tribe but they were practicing shamanism. The well-known Native American scholar, Paula Gunn Allen, states:

In the old days, most, if not all, of the members of a given tribal society were initiated in at least a few methods for achieving mystical awareness. In every tribal society, girls were trained in the mystical responsibilities that fell to every woman and were at least aware that special mystical states and responsibilities were privy to certain holy women and female ritual leaders. Similarly, every boy learned his spiritual and mystical responsibilities and was aware that certain men experienced special states.

Thus while mysticism in the West is a kind of special experience familiar to only a few, all Native American peoples feature various disciplines and practices by which mystical power is sought, and to some extent virtually every individual is a seeker or a holy person, and in some sense many are both. Among the disciplines widely practiced - and usually considered central to spiritual seeking - were dreaming, vision-seeking, purification, fasting, praying, making offerings, dancing, singing, making and caring for sacred objects, and living and good and varied life (Allen, 47)[Emphasis added].

These rocks were seen as interdimensional portals. Whitley says the rocks were seen as entrances to the supernatural world and Parkman says that the baby rock ritual actually included "movement through rock."

In fact, the ONE and only thing that we DO know that these cultures have/had in common is shamanism. Although the subject of diffusionism cannot be ignored and is not mutually exclusive to shamanism either:

“The resemblance of these American cup-and-rings with the European examples is striking (Morris 1988) but although even Palaeolithic seafarers apparently acquired the ability to cross open ocean with ease(Bednarik 1996: 122), it is doubtful whether there once existed a link between these two manifestations of cup-and-ring execution. But still, was Europe once influenced from the Americas ?” (Van Hoek 227).

Anthropologist, Barbara Tedlock, studied with Pomo medicine women, Essie Parrish and Mabel McKay. In The Woman in the Shamans Body, Barbara Tedlock discusses, “the startling similarities between shamanistic ideas and activities in cultures as far apart of Siberia, the Amazon Basin, Southeast Asia and Nepal. Birth and death provide key actions and metaphors within these shamanic systems, and novice shamans are said to be “born into” or “to die into” the profession. Later in their subsequent practices, they may assist in actual births and deaths” (Tedlock 27).

Judy Grahn adds, "If the human comprehension of death is metaformic, our approach to illness and healing is equally part of the menstrual mind. Shamans and other tribal healers were often women; some think originally all healers were often women" (Grahn 127). Jeannine Davis-Kimball underscores the point, "The Russian ethnographers, who were among the first to study the Siberian peoples, maintain that the first shamans were women, but as shamanism displaced the priestess cults and assumed greater influence in tribal affairs, men began to dominate the profession in Siberia and Central Asia" (Davis-Kimball 85).

Tedlock insists that, “To truly comprehend the healing potential of women’s blood, we need to pay closer attention to traditions in which women practice as shamans” (Tedlock 203). “Women on feminine [shamanic] paths focus their attention around birth. They receive their shamanic calling during menarche or pregnancy and are symbolically born into the profession” (Tedlock 202). Tedlock notes that in many cultures there is an overlap between midwives and shamans and that in those cultures midwivery is usually considered a branch of shamanism.

"Women shamans are nearly always midwives. The act of helping sould transform themselves in order to cross from the other world into this world turns out to be at the heart of feminine shamanic traditions worldwide. While the masculine traditions focus on a shaman’s symbolically dying into shamanhood, the feminine traditions focus on the shaman’s being born into it. For that reason pregnant women and new mothers all over the globe are often inspired to become prophets, diviners, healers or shamans” (Tedlock 206).

Monica Sjoo, emphasizes, "The birthing woman enters an altered state, hovering as she does between life and death, this is the original mystery and the first shamanic experience" (Return of the Dark/Light Mother, 281).

"Fertility wisdom and shamanism are about crossing between the worlds. The birthing woman is the archetypal shaman...as she brings the soul from the other realms into this world, forming and incarnating it within her body. She is mediator between the worlds and magically converts bread and wine into flesh and blood in mysteries of transformation" (Return of the Dark/Light Mother, 173).

Whitley's discussion of shamanism and rock art seems a bit contradictory. He even states, "This might seem contradictory, in that Pit and Groove Tradition art neither was made by shamans nor involved states of consciousness and visionary imagery. Yet its foundation in shamanistic beliefs and rituals were tied in basic ways to the larger shamanistic complex: rocks and thus rock art sites were entrances into the supernatural world and therefore places from which power could be obtained." (Whitley 98).

Parkman argues, however, that fasting during this ritual did effect an ASC (altered state of consciousness) for these women. I would also add that the ritual itself and the repetitive elements of the ritual including chipping away at the rock are also consciousness altering.

The most likely origin of the commonalities in rock art worldwide is that shamanism and its associated ASC's seem to be rooted in one common denominator: human biology.

Many scholars “argue for a ‘pan-human’ cognitive system,” grounded in the practice of shamanism (McCall).

Students of prehistory have long “been aware of a series of putative universal shamanic symbols” (Whitley article, 2). They attribute these “persistent cross-cultural symbols” to “universal psychologisms” which, Whitley points out leads to an ontological contradiction: “ how can non-material mentalist phenomena have material consequences?

Whitley proposes a resolution to this ontological paradox – these symbols may “have their origins in natural models. They are based on shared neuro-psychological and somatic reactions to altered states of consciousness (ASC’s) and to certain drugs or substances [I would add practices] that relate to ASC’s. Because their origin lies in physical responses to ASC’s it is then apparent that this symbolism is not psychologistic or mentalist in origin … cultures and societies may have changed but universal reactions to ASC’s were and are constant. “Achieving an ASC (held to represent entering the supernatural realm) is a defining characteristic of shamanism, cross-cultural experience mental imagery has important implications for shamanic iconography" (Whitley article, 2).

Whitley maintains that “ethnography demonstrates rock art in the far west was created to graphically depict visions received during ASC’s" (Whitley book 3), or "the depiction of the visionary experiences of the supernatural world, especially spirit helpers, by shamans and others seeking shamanistic power. For the non-shamans this practice was limited in its freqeuncy and intensity, and the resulting rock art was relatively simple in composition and, for any single individual, repetitive in form. Shamans, however depicted larger number of spirit helpers, and other activities they conducted while in the supernatural. In either case the making of a 'dream picture' was part of a very widespread tradition of illustrating an individuals spirit helpers" (Whitley book, 98).

“In all instances rock art sites were considered to be numinous and were believed portals to the supernatural realm" (Whitley article, 4). For groups in the Far West “entry into the supernatural was thought to be a spiritual movement into a sacred realm that paralleled the mundane, temporally and (in a sense) geographically and was viewed as a very distinct from the world of myth…” (Whitley article, 6).

“Far Western North American shamans (and ritual initiates) did not see “mythic beings” nor “portray them in their rock art, but instead visited a supernatural realm, and received supernatural sprits that were quite distinct from myth and mythic actors.”

Rock are sites “do not illustrate mythology for some didactic purpose but instead are “shamans’ spirit helper places” (Whitley article, 6).

“no distinction was made between the dreams of a normal nights sleep and ASC’s (both were simply termed dreams).” Whitley finds a metaphor for ASC’s in sexual intercourse and says that in the rare times it shows up in the ethnographic literature its sometimes “used metaphorically as connoting a supernatural experience,” although ritual intercourse itself could occur during ASC’s” “Bedrock mortars were said to have their origin when in mythic times coyote had intercourse with a rock. Here the symbolism is obvious: pestle =penis, mortar = vagina, creation of hallucogen = intercourse. And in Northern California, women having difficulty conceiving would grind small cupules, into a rock and then ingest the rock powder, that is, like Coyote, they would have ritual intercourse with a rock” (Whitley article, 21).

“Rock art sites were feminine gender places,” although “they were often used by men.” (whitley book, p.98) as female symbols were by no means only used by women (quoting barrett) according to Barrett, they would sometimes use vulva form motifs in “female places.” (p.100-101)

The Bradshaw Foundation states: “Very frequently cupules have feminine connotations, being associated with the vulva [J.Clottes 2002]. The 'Baby Rocks' at Keystone in California get their name from the fertility rituals practiced by the Hokan Indians at these sites. It was believed that the rock powder generated in hollowing out the cupule would facilitate conception when placed in a woman's body before she had coitus” (Bradshaw Introduction).

“Rocks and rock art sites were equated with vaginas and women in part this was due to the similarity between caves and vaginas, though this symbolic association was also based on deeper concepts and physiological attributes of altered states of consciousness. There is also physical analogy between pounding or grinding an indentation in a rock, using a pestle, and sexual intercourse .” (Whitley book, 100)

Sjoo and Mor note:

Among people for whom sex does not imply impurity, or hold magico-religious danger, the taboo on the sexual act does not occur in relation to ceremonies. Rather, ceremonial sex was always a powerful act leading to spiritual perfection. Within the stone circles of the Neolithic, perhaps the entire human community celebrated the creative power of the Goddess, in festivals coinciding with those magic times when the energy-tides of the unseen flowed strongly around and through the earth. Earth-channels were then wide open to receive to receive her spirit, giving enhanced consciousness, healing, and fertility to the people. These are the ceremonies that have been condescendingly labeled "fertility rites" by prurient patriarchal anthropologists, and "satanic orgies" by the missionaries(Great Cosmic Mother, 152).

Pomo baby rocks are a classic example of ancient and contemporary female shamanism.

These rocks are still used to this day. Due to the secrecy of the ritual, we don't know how many Pomo may still be using these rocks, but biologist, Jim McKissock told of a time when, "a pregnant woman who feared a cesarean birth came to the [East Bay] rock to meditate. Later, her waters broke, and she delivered by natural childbirth."

The baby rocks are still being used in Hawaii, as well. "Whilst researching a cupule site in Hawai'i where cupules had been carved within the past 10 years, Dr Georgia Lee broke for the rainy season. She returned to the site to find that 3 new cupules had been added in her absence. Sensing desecration, she tackled the Chief who laughed and informed her that three births had occurred in her absence and that the mothers had individually ground the scab from the navel of the baby into the rock, creating a cupule in an Earth goddess ritual."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Paula Gunn. Off the Reservation: Reflections on Boundary-Busting, Border-Crossing Loose Cannons. (Boston: Beacon Press), 1998.

Aginsky, B.W. “Population Control in the Shanel (Pomo) Tribe.” American Sociological Review, vol. 4, no. 2 (April 1939): 209-216.

Answers.com, s.v. Pomo people, Wikipedia, 2005. http://www.answers.com/topic/pomo-people

Berton, Justin.“This Rock May Help You Get Pregnant.” East Bay Express, July 28, 2004. http://www.eastbayexpress.com/Issues/2004-07-28/news/eastsidestory_print.html

Bibby, Brian. Precious Cargo: California Indian Cradle Baskets and Childbirth Traditions. Berkeley: Heyday Books & Marin Museum of the Native American, 2004.

Bradshaw Foundation. International Newsletter on Rock Art #43, http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/inora/meeting_43_2.html

Bradshaw Foundation. Introduction. http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/twyfelfontein/intro.html

Burnham, Andy. The Megalithic Portal. http://www.megalithic.co.uk

Cloverdale Historical Society http://www.cloverdalehistoricalsociety.org/CHS_new/Cloverdale/history.htm

Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. Warrior Women: An Archeologist’s Search for History’s Hidden Heroines, (New York: Warner Books), 2002.

Foster, Daniel G. “A Note on CA-MEN-1912: The Spyrock Road Site, Mendocino County, California.” Rock Art Papers, vol. 1, edited by Ken Hedges, San Diego: San Diego Museum of Man, 1983.

Friends of Baxter Creek. http://www.creativedifferences.com/baxtercreek/creekhistory.html

Hedges, Ken. “The Cloverdale Petroglyphs.” Rock Art Papers, vol. 1, edited by Ken Hedges, San Diego: San Diego Museum of Man, 1983.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess. San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1991.

Grahn, Judy. Blood, Bread, and Roses. Boston: Beacon Press, 1993.

Heizer, R.F. and M.A. Whipple. The California Indians: A Sourcebook. London: University of California Press, 1971.

Lake, Tela Star Hawk. Hawk Woman Dancing with the Moon. New York: M. Evans & Co. Inc. 1996.

Loeb, Edwin M. “Pomo Folkways.” University of California Publications in American Archeology and Ethnology, vol. 19, no. 2, 246-248. Berkeley: The University Press, 1926.

Lopez, Alan. “Clues to Area's Past Set in Stone.” The Journal. January 3, 2003. http://www.creativedifferences.com/baxtercreek/news03.html

Lopez, Alan. “Group Seeking Clues to Carvings,” The Journal, June 18, 2004. http://www.creativedifferences.com/baxtercreek/news03.html

Marymor, M. Leigh. “Rock Art Conservation at Canyon Trail Park, El Cerrito, California (San Francisco Bay Area).” La Pintura: The Official Newsletter of the American Rock Art Research Association, vol. 30, no. 1, August 2003. p. 1-3. http://www.arara.org/pdf_standard/LP-30-1.pdf

Marymor, M. Leigh. “Cupule Bibliography,” posting to Rock Art Discussion and Information, Arizona State University list-serv, March 9 1996, http://lists.asu.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind9603&L=rock-art&D=1&F=&S=&P=2379

Mauldin, Henry K. Our Lakes, Valleys & Mountains: History of Lake County. San Francisco: East Wind Printers, 1960.

McCall, Grant S. One Medium, One Mind: A Personal View of Rupestrian Archeology,1996. http://www.geocities.com/athens/forum/3339/rockart.html

O’Brien, Kathy, Donna Gillette, and Roger Kelly. “Excavation at a Petroglyph Boulder: Canyon Trail Park, CA-CCO-152,” Proceedings of the Society for California Archeology. http://www.scahome.org/publications/past_proceedings/Proceedings.Abstracts.18OBrien.htm

Parkman, E. Breck. “The Supernatural Frontier in Pomo Cosmology.” California Department of Parks & Recreation, 2004. http://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=23014

Rigoglioso, Marguerite. “Persephone's Sacred Lake and the Ancient Female Mystery Religion in the Womb of Sicily,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 21.2 (2005) 5-29. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/journal_of_feminist_studies_in_religion/v021/21.2rigoglioso.html

Roach, Mary.“Ancient Altered States.” Discover, Vol. 19 No. 06, June 1998. https://www.discover.com/issues/jun-98/features/ancientalteredst1456/

The Stone Age in Israel: Brilliant sculpture from Sha'ar Hagolan

Copyright 1999 by Jacqueline Schaalje

http://www.jewishmag.com/24MAG/SHAAR/shaar.htm

Sjoo, Monica and Barbara Mor. The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth, New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1991.

Sjoo, Monica. Return of the Dark/Light Mother or New Age Armageddon?: Toward a Feminist Vision of the Future (Second, Revised Edition), Austin, TX: Plain View Press, 1999.

Tedlock, Barbara. The Woman in the Shaman’s Body. New York: Bantam Books, 2005.

StoneWatch

The World of Petroglyphs (CD Special 4) - Copyright by StoneWatch 2001

Special 4 The Geography of Cup and Ring Art in Europe

by Maarten van Hoek, Oisterwijk / Nederland

Computerworks by StoneWatch http://www.freemedia.ch/downloads/005.pdf

Varner, Gary. Menhirs, Dolmen and Circles of Stone: The Folklore and Magic of Sacred Stones. http://www.authorsden.com/categories/article_top.asp?catid=37&id=11836

Whitley, David S. “Shamanism, Natural Modeling and the Rock Art of Far Western North American Hunter-Gatherers.” Shamanism and Rock Art in North America, edited by Solveig A. Turpin, 1-43. San Antonio: Rock Art Foundation, Inc. 1994.

Whitley, David S. The Art of the Shaman. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2000.

Winegarner, Beth. Sacred Sonoma: Sacred Sites and Alignments in Sonoma County California (internet version). http://www.sacredsonoma.com/

Photo Credits:

Pomo girl photographed by Edward S. Curtis in 1924, in the public domain via

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/curthome.html

and wikipedia.org

Austin Creek Basin

http://www.sacredsonoma.com/chapter2-4.html

Fertility Rock in Somaliland by Ken Njuguna

http://www.insidesomaliland.blogtales.com/archives/000127.html

Photo locations links and credits:

The Dobrudden Stone at Baildon Moor, in Yorkshire, England. BELOW:

http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=5170

Alvarado Park http://www.rcoc.com/history.htm

El Cerrito pix http://www.arara.org/pdf_standard/LP-30-1.pdf

Archeo-Tec, Consulting Archeologists

Santa Clara County http://archeo-tec.com/sites/califmap.php?x=boulderridge

Lake County - http://www.chargedbarticle.org/baby_rock.htm

Ring Mountain - http://www.gatetrails.com/photos/ringmountain10.jpg

2nd photo - http://www.gatetrails.com/impressions/ringpetroglyphimp.jpg

Rock Art News

ALVARADO PARK, CA-CCO-125, RICHMOND

and CANYON TRAILS PARK,

CA-CCO-152, EL CERRITO, CONTrA COSTA COUNTY. SAN FRANCISCO BAY

AREA. CALIFORNIA.

“Excavation at a Petroglyph Boulder: Canyon Trail Park, CA-CCO-152”

http://www.scahome.org/publications/past_proceedings/Proceedings.Abstracts.18OBrien.htm

Universal stone and fertility lore –

http://www.authorsden.com/categories/article_top.asp?catid=37&id=11836

near pre-historic Jerusalem

http://www.jewishmag.com/24MAG/SHAAR/shaar.htm